In the countryside of East Germany, I found a story of earth, water, air, and fire.

Remnants of glacial lakes left behind after the last Ice Age formed rich clay deposits in this region over millennia. These deposits lay undisturbed beneath dirt and forest until the 13th century when Flemish monks popularized the use of burnt bricks, growing the demand for clay.

Centuries later, a construction boom swept through Berlin. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, the demand for bricks brought brickworks (Ziegelei in German) to this area's clay deposits. Buildings were rising, roads were being paved, and Berlin was rapidly transforming into a metropolis. The bricks found their way into the heart of this transformation.

Multiple generations of brickworks have operated in the region, each adapting to the technologies of their time. From hand-molded bricks fired in simple kilns to the industrial-scale production that remains abandoned at the site today.

The following is how earth, water, air, and fire came together to create a brick.

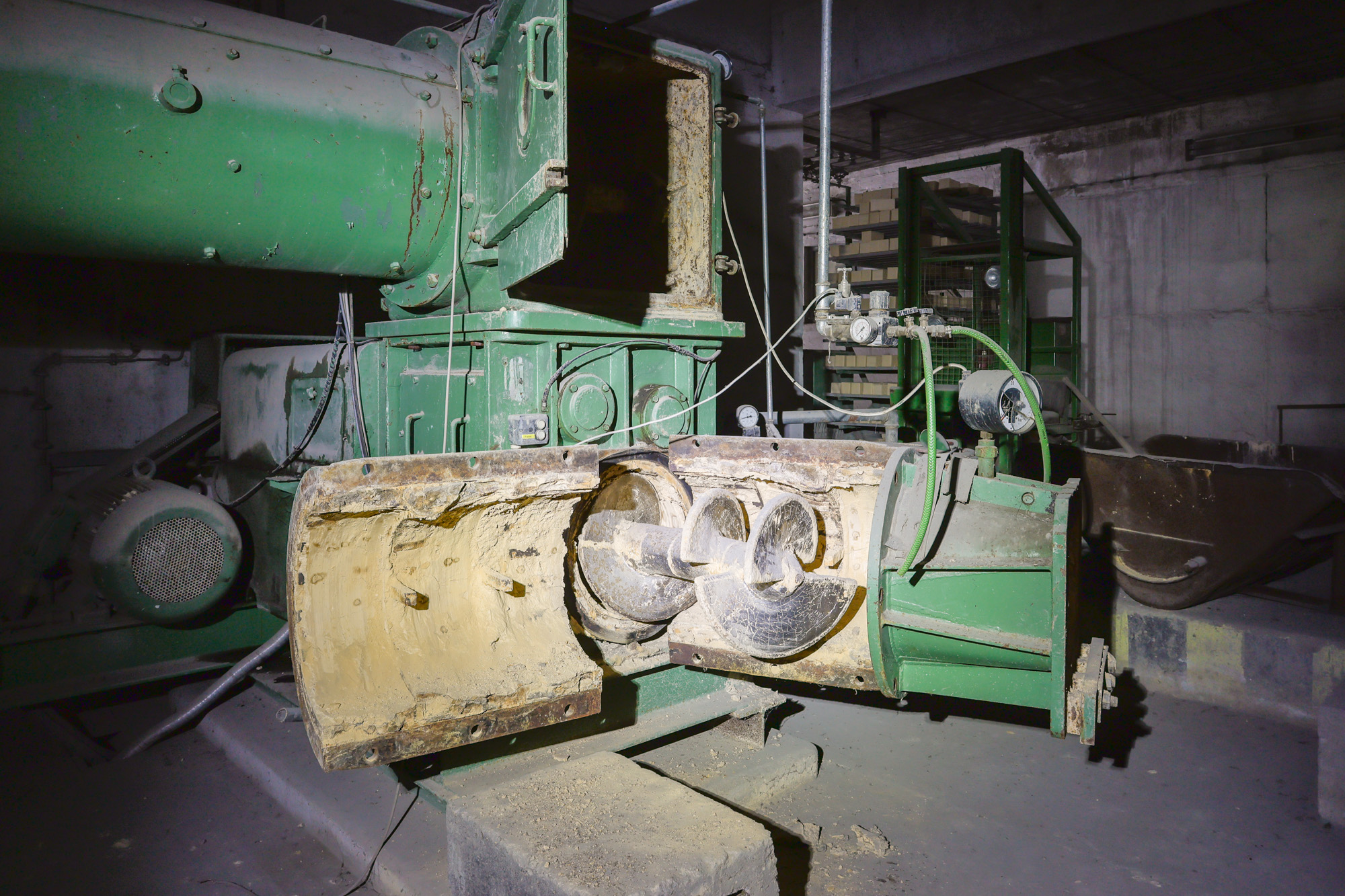

Clay from local excavation sites was brought to Brickworks Fasskessel, where it was fed into a series of buildings via conveyor belts. Here, the clay was mixed with water and processed by various machinery before being extruded into rectangular slugs.

Next, the slug was sliced by a metal wire, with each cut spaced around 8% wider than the thickness of a brick, to account for shrinkage during drying.

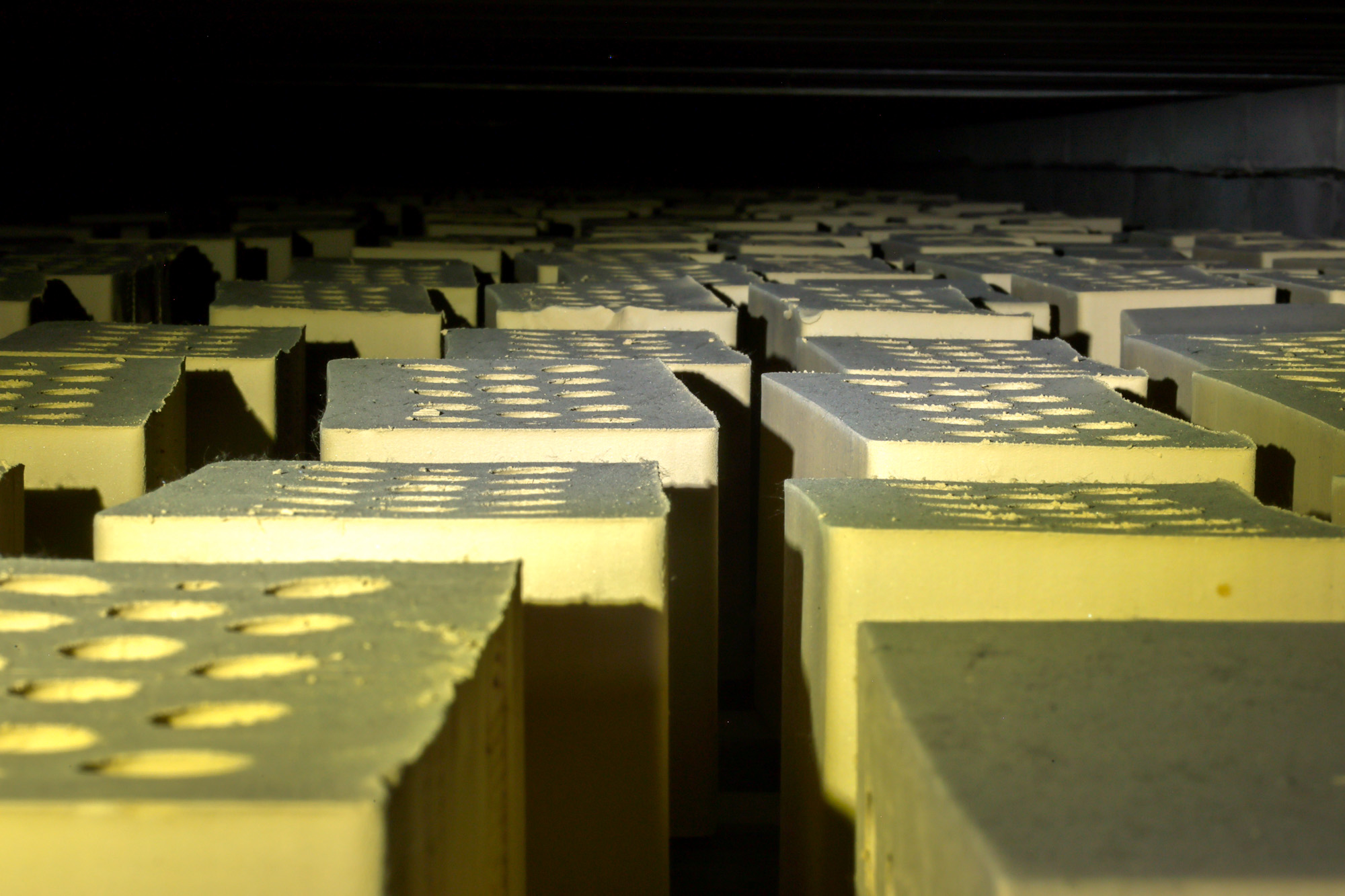

After slicing, the wet bricks were arranged by conveyor belts into rows, positioned on bars made of refractory materials like cordierite and silicon carbide. These materials could withstand the high temperatures inside the kiln without deforming or breaking.

Eight bricks to a row, four rows to a layer, ten layers to a column, and at least sixteen columns to a kiln—allowing for well over 5,000 bricks to be baked in a single kiln.

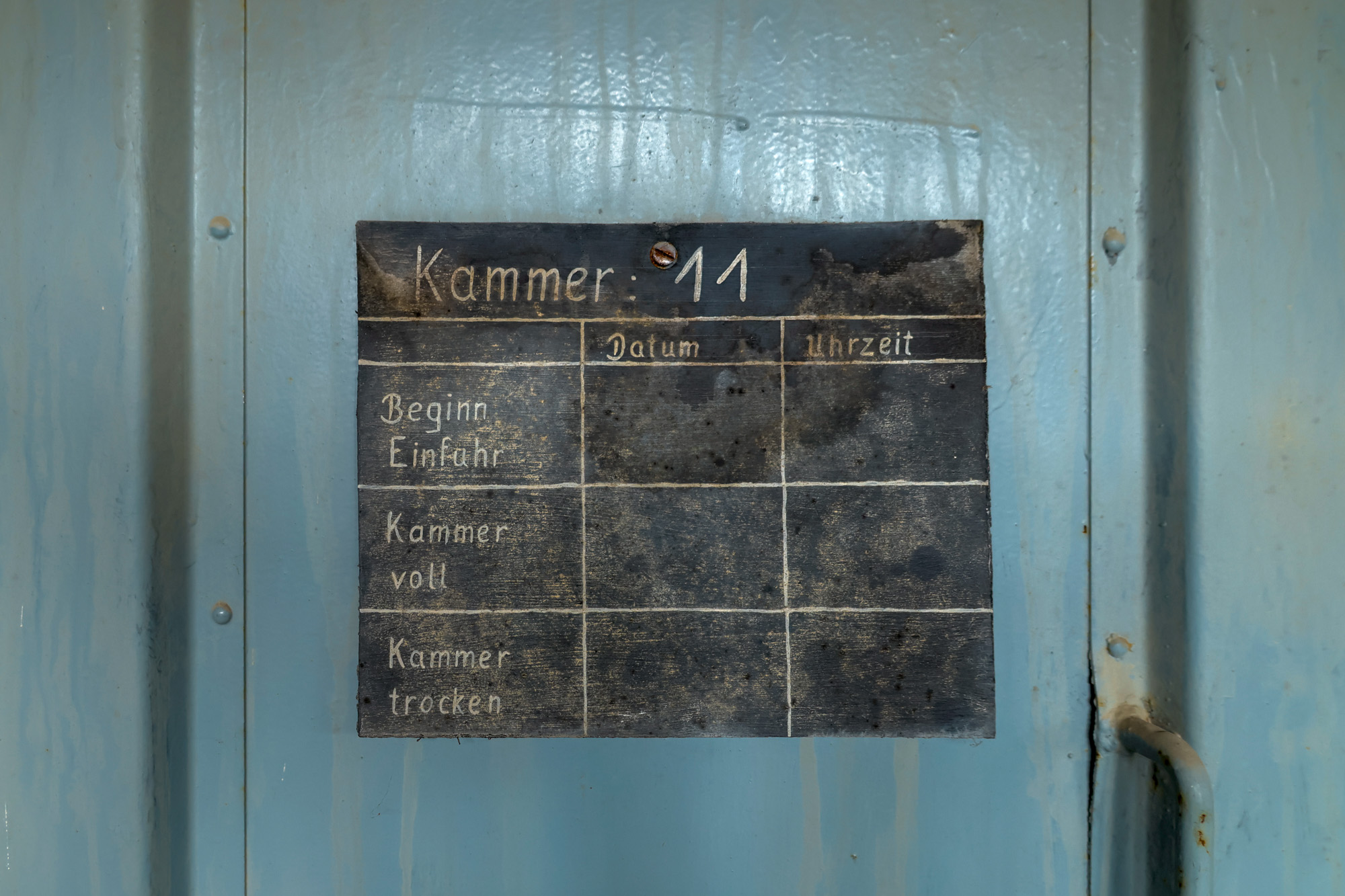

This modern kiln building has 40 kilns. Some are still full of half-fired or un-fired bricks today. Their chalky texture instantly lets you know this is not a finished brick, instead a fragile object that can be easily smashed (by vandals who had previously visited) or dissolved back into soft clay (when in contact with intruding rain water).

Each of the kilns could be individually operated and temperature-controlled from gauges, values, and handwheels on the back side. Each pipe mixed air and gas together to create fire and heat to transform earth and water into a brick.

Also on this site is a remnant of an older style of brick production. This ring oven was built in the year 1890 and provided the space and plumbing to likely fire more bricks than all the new ovens combined in a single go. Unfortunately, today it sits just as abandoned as its newer counterpart next door. If your interested in learning more about ring ovens, checkout this great article from LOW←TECH MAGAZINE.